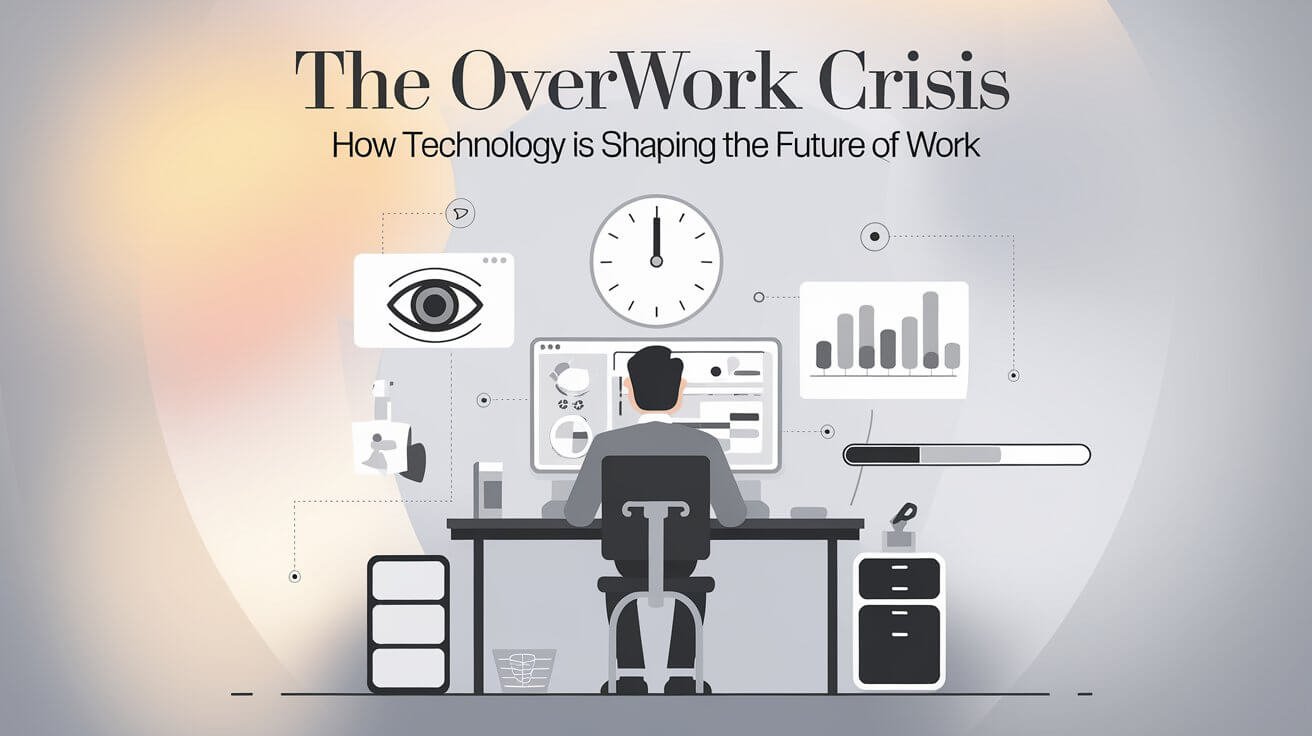

The Overwork Crisis: How Technology, Inequality, and Cultural Shifts Are Reshaping the American Workweek

Introduction

In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes envisioned a future where technological advancements would lead to a dramatically shorter workweek—just 15 hours. Nearly 100 years later, however, the reality is starkly different. Americans are working longer hours than ever, with nearly 40% of full-time employees clocking in over 50 hours per week, and 18% working 60 hours or more. This article explores the causes behind this “overwork crisis,” including technological control, economic inequality, and cultural shifts. We’ll also look at potential solutions to restore balance and make the promise of a shorter workweek a reality.

The Origins of the Overwork Crisis: A Historical Overview

The idea of reducing working hours has been tied to economic progress and technological advancement for decades. However, instead of working less, many Americans are now working more, with labor hours steadily increasing since the 1970s. Between 1975 and 2016, American workers’ hours grew by 13%, or the equivalent of five extra weeks of work per year. This shift occurred simultaneously with rising income inequality, the decline of unions, and skyrocketing housing prices. For many, the only way to keep up with the cost of living was to work longer hours.

In fact, compared to workers in other developed countries, Americans work significantly more. On average, Americans work six hours more per week than the French and eight hours more than the Germans, which amounts to nearly two additional months of work per year based on a 40-hour week.

The Strain on Low-Wage Workers: A Personal Story of Overwork

While overwork affects many, it is most acutely felt by low-wage workers. Consider Amanda, a home health aide in Vermont. Despite working 60 hours a week and holding a second job at a travel agency, Amanda’s hourly wage remains stagnant at $11.12—well below the federal poverty line. Her situation is hardly unique; many low-wage workers have no choice but to take on multiple jobs just to survive.

Fact: Over the past four decades, corporate CEO compensation has skyrocketed by 1,070%, while average workers’ hourly wages have risen only 12%. Meanwhile, the cost of living, particularly housing, has increased dramatically—forcing workers to work longer hours just to maintain their standard of living.

This growing income disparity is a key driver of the overwork crisis. For millions of workers like Amanda, a rising cost of living coupled with stagnant wages has led to a vicious cycle of long hours and financial strain.

Technological Control: Surveillance and Productivity

The 21st century promised technological advancements that would reduce the burden of work, yet technology is now being used to intensify surveillance and control in the workplace. A prime example of this can be seen at companies like Amazon, where employees like Nicole Calhoun face intense electronic monitoring. Nicole is required to walk up to 24 kilometers per night, scanning thousands of items at a fast pace. Her handheld scanner tracks each movement, and workers are penalized if they don’t meet the target of 125 picks per hour.

Even workers in white-collar jobs aren’t immune to this trend. Software like TerraMind tracks employees’ every move—monitoring keystrokes, taking pictures every ten minutes, and recording email activity. While high-income workers may have more control over their hours, they too face a growing level of surveillance.

Quote: “Technology was supposed to free us from the tyranny of long work hours, but instead, it has become a tool to monitor and control workers in unprecedented ways.”

This technological control is not just about monitoring productivity; it’s about shaping every aspect of the work experience—dictating how, when, and where employees perform their tasks.

The Cultural Shift: Work as the Ultimate Value

In addition to economic and technological forces, cultural changes have played a significant role in the rise of overwork. As early as the 1960s, only 6% of Americans believed that work was central to their success; by 1982, that number had increased to 49%. This shift in mindset was amplified by figures in Silicon Valley, like Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs, who promoted the idea that “work itself is the reward.”

This cultural shift came at a time when wages were stagnating, and employers were looking for new ways to motivate workers. By framing work as a meaningful and fulfilling activity in itself, employers could reduce the need for higher wages while still motivating their workforce to work longer hours.

Statistic: Today, the average American works six hours more per week than the French, and eight hours more than the Germans—equivalent to two extra months of work annually.

As a result, many workers have come to see longer hours as a measure of their success, even as wage growth stagnates and living costs rise. The expectation of overwork has become normalized, turning it into a badge of honor in many industries.

Government Policies and the Erosion of Worker Protections

Government policies, particularly from the 1990s onwards, have further exacerbated the problem of overwork. The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) introduced stringent work requirements for welfare recipients. While the law reduced the number of people receiving welfare, it also contributed to a rise in working poverty, with many workers being forced into low-wage, unstable jobs without adequate benefits or opportunities for advancement.

Moreover, programs like New York’s Work Experience Program (WEP) pushed welfare recipients into low-wage work without providing pathways out of poverty. While the intention was to encourage self-sufficiency, the reality was that many people found themselves trapped in jobs that didn’t pay enough to live on.

Solutions: A Path to a Healthier Workweek

While the problem of overwork is systemic, there are solutions that can help address this crisis. One of the most effective ways to combat overwork is through collective action. In Philadelphia, for example, retail worker Terrence helped pass fair scheduling laws that provide workers with advance notice of their schedules—benefiting 130,000 workers in the city. These laws have since spread to seven other cities.

Similarly, unions have played a crucial role in protecting workers’ rights in the face of technological change. When Kaiser Permanente introduced new technologies, unions negotiated agreements that protected workers’ wages and jobs while preparing them for new roles.

Potential Solutions:

- Work-sharing programs: These programs allow companies to reduce work hours while maintaining employees’ income, helping to combat unemployment and ensure that workers maintain their standard of living.

- Universal basic services: These could include free healthcare, education, childcare, and housing—reducing the financial pressure that forces workers to take on more hours.

- Stronger worker protections: Legislation that ensures workers are not subject to excessive hours or invasive surveillance, and that guarantees fair wages and benefits.

Ultimately, the overwork crisis is a systemic issue, not a personal failure. It requires collective action and policy change to address the underlying causes: economic inequality, technological control, and cultural expectations of work.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Our Time and the Promise of Technological Progress

The promise of a shorter workweek, heralded by Keynes nearly a century ago, has yet to materialize. Instead, many workers find themselves trapped in a cycle of overwork, driven by economic inequality, technological surveillance, and cultural pressures. However, by pushing for stronger worker protections, advocating for fair labor laws, and prioritizing a healthier work-life balance, we can begin to reclaim our time and make the promise of a shorter workweek a reality.